On January 24, 2008, Professor Stephen Vasciannie delivered the Cobb Family Lecture entitled The Human Rights Project in Jamaica. With the kind permission of Prof. Vasciannie, the text of his lecture is reproduced here. Please respect Prof. Vasciannie's copyright!

The Cobb Family Lecture

The Human Rights Project in Jamaica

Chairman, Ambassadors Cobb and LaGrange Johnson, Members of the American Friends of Jamaica, Public Defender, Specially Invited Guests, Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen:

I am grateful for the opportunity to give this lecture today. Ambassador Cobb: this lecture is a tribute to you and to the important work you did while you served as the United States ambassador to Jamaica. As has been said, you were a frank, hard-working and successful ambassador here. You have been a friend of the University, and I remember, for instance, that you were instrumental in arranging of the seminar in honour of Ralph Bunche in collaboration with the Department of Government at Mona. I also recall that a number of lecturers in the Department of Government participated in various activities with the American Government during your period of stewardship, particularly in respect of hemispheric security questions. Ambassador Johnson has continued the tradition of good relations between the United States Government and the University; the good relations are evident from Ambassador Johnson’s presence here today. I would also like to thank Dr. Gossell Williams for the determination and organization skills that she has put into the Cobb Lecture.

My presentation is about human rights. From the outset, I wish to acknowledge, with gratitude, the persons who have contributed significantly to the human rights project in Jamaica. For many years, the Independent Jamaican Council for Human Rights, under the leadership of Dr. Lloyd Barnett and with persons such as Dennis Daley and Nancy Anderson, has done sterling work in the field. Similarly, Hilaire Sobers and Mrs. Yvonne McCalla Sobers have made major contributions, and remind us in various ways that if the State abuses your rights today, they will abuse mine tomorrow. They all remind us too that human rights principles must be available to all without fear or favour.

What is the state of human rights in Jamaica today? Naturally, the responses to this question will vary from person to person. What is striking, though, is the deep chasm that appears to exist between the perspectives of the optimists and pessimists on this question. The optimists are inclined to argue that Jamaica, for all challenges, has made considerable progress in the area of human rights. For them, the country has a constitutional system that enshrines fundamental rights and freedoms; these rights and freedoms are respected in large measure by the State; the State does not willfully seek to violate individual rights; and where breaches of human rights are perpetrated, the State and its institutions try to effect remedies in the interests of victims.

In contrast, the pessimist is apt to argue that the constitution does not do enough to ensure human rights, and that, in any event, even the stated constitutional safeguards are given only limited effect in practice. Sometimes it seems that the human rights debate is not over whether the glass is half-full or half-empty: it is more about whether the glass exists any at all.

The gap between how the State views its performance in the area of human rights on the one hand, and how Jamaican citizens rate the State, on the other, has not been fully explored in the literature pertaining to Caribbean law and politics. It is, however, a point that will be familiar to most denizens of the Region, and certainly of Jamaica. Various Ministers of Justice in Jamaica have made State of the Nation Addresses and other pronouncements confirming the State’s commitment to human rights, and have, as a matter of policy, insisted that the Jamaican Government should respond officially to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the United Nations Human Rights Committee and other bodies on all issues pertaining to the promotion and protection of human rights in Jamaica.

In short, they have accepted that Jamaica should adhere to the rule of law. But the gap is evident, for, notwithstanding official pronouncements and responses, the people of Jamaica also know about the situation in the street: “de runnings” as we are inclined to call them. And on the street, the perception is frequently that the most basic human right – the right to life – can be taken with impunity by some members of the security forces. So, objectively speaking, the State is challenged: it wants one thing, and offers the rhetoric in support of that goal. But, for reasons that will be canvassed below, some of the State’s agents want something different, and armed with guns, these agents are prepared to violate the law, to take life unlawfully.

Against this background, questions concerning human rights are of considerable interest in Jamaica. In this presentation, I wish to consider the main factors that influence the perception and the reality concerning human rights in the country. My intention is to provide some ways of thinking about human rights issues in the country: you know much of the text, but I will offer some elements of context. I will do this by looking at a series of propositions about human rights law and practice.

(1) The Constitution does not deliver on its promise.

The Jamaican Constitution provides an important foundation for the promotion and protection of human rights in the country. Chapter III of the Constitution – on fundamental rights and freedoms -- sets out a substantial list of civil and political rights. These rights are expressly said to trump any legislation or other State action, so that if the Government passes a law that is in conflict with any one of the fundamental rights and freedoms, that law will be null and void to the extent that it conflicts with Chapter III. This foundation is important not only because it provides State agents with advance notice as to how far they may go in seeking to curtail individual rights, but also because it represents a statement by the society as to what we recognize as our most significant values. Subject to certain qualifications, the main human rights so recognized in the Jamaican Constitution are as follows:

(a) The right to life;

(b) The right to liberty;

(c) Freedom of movement;

(d) Protection from inhuman treatment;

(e) Property rights;

(f) Protection for privacy of home and other property;

(g) The protection of law;

(h) Freedom of conscience;

(i) Freedom of expression;

(j) Freedom of assembly and association;

(k) Protection of discrimination on grounds of race, , place of origin, political opinions, colour or creed.

This list therefore serves as the starting-point for our understanding of human rights in Jamaica, and to that extent, it must be recognized as key to the promotion and protection of rights. Indeed, given that it incorporates most, if not all, of the civil and political rights recognized in Western societies, it may be regarded as a promising foundation.

On closer examination, however, the provisions of Chapter III of the Constitution, are subject to noteworthy criticisms from a rights perspective. To begin with, Chapter III is formulated in terms of “lawyers’ law”. Thus, some of its provisions are not easy to understand, and in several places the basic human rights are subject to qualifications that require careful analysis.

To take one example, we all share the view that everyone is entitled to liberty, and in practice, we are inclined to view incursions into that right as violations on the part of the State. But the Constitution takes a detailed approach to the question of liberty; so, after stating the basic principle, it goes on to enumerate at least eleven circumstances in which personal liberty may be restricted. These include, among others: unfitness to plead a criminal charge, the execution of a court sentence for a crime, imprisonment for contempt of court, detention before trial, detention on suspicion of having committed a crime, detention of minors for the purpose of education or welfare, detention to prevent the spread of an infectious or contagious disease, detention for the care or treatment of persons of unsound mind, addicted to drugs or alcohol, or vagrants, and detention to prevent unlawful entry or to ensure expulsion or extradition.

Now, on the face of things, most of these restrictions are reasonable in the sense that they help to preserve the interests of both individuals and the State; however, when all these qualifications are juxtaposed immediately against the principle that “no person shall be deprived of his personal liberty”, one may wonder about just how much of the principle is left.

In some cases, too, the rights provisions in Chapter III of the Constitution are limited by general language that cuts down the capacity of the provisions to promote and protect the cause of individual freedom. To be more specific, the Constitution guarantees freedom of movement, the right to privacy of home and property, freedom of conscience, freedom of expression and freedom of assembly and association; the relevant provisions give the impression, then, that each of these rights is of great social value, to be limited only on an exceptional basis. But, in fact, each of these rights is curtailed by general language to the effect that the rights may be trumped by any law “which is reasonably required in the interests of defence, public safety, public order, public morality or public health.” This proviso means that as long as the State may reasonably argue that it has to limit basic human rights for reasons of defence and so on, the rights may be reduced to nothing. There is an understandable logic to this approach, for with respect to defence, public safety, public order and public health, the founding fathers of the Constitution could reasonably have decided to attach greater significance to collective rights than to the human rights of the individual person.

Even so, however, the approach taken to collective rights is vulnerable to criticism in at least two respects. First, because the exceptions are so general, the State is arguably given too much latitude: in effect, the only limit on the State here is that the restrictions are “reasonably required”. For some, this requirement is quite vague and it allows the State to take action that may only be challenged ex post facto. There, therefore, is no clear attempt in the Constitution to emphasize that restrictions on freedoms such as movement, conscience, expression and assembly are fetters to individual liberty, to be treated as highly exceptional.

Second, the exception for “public morality” may be open to particular criticism. Clearly, in some cases private and public morality may differ; and if this is the case, what is the underlying principle by which it is ordained that public morality must always prevail as a matter of law? The jurisprudence of human rights in some other jurisdictions has tended to attach increasing significance to private morality, largely on the basis that if what you do does not harm other persons – relying on Mill and Hart – then the law has no place in restricting your behaviour.

Without expressing a final view on whether private morality should necessarily trump public morality, it seems to me that the Jamaican Constitution has turned the issue on its head: it suggests that public morality, as determined by the State, may always trump freedom of expression, freedom of conscience, and the right to privacy, as long as this is believed to be reasonably required. In short, the Constitution limits the scope for debate about how far moral concerns should enter our assessment of laws by allowing the State to defend restrictions on human rights on the ground that the rights are inconsistent with the inherently vague concept of public morality. Suppose, for example, a man adheres to religious practices that hurt no one, but which may be contrary to the majority, Christian traditions in the country: should the State be able to prohibit these practices on the basis that prohibition is reasonably required to preserve public morality? Freedom of conscience suggests one answer, the public morality exception suggests another.

The Constitution, though starting with the premise that we all have fundamental rights and freedoms, does not fully live up to the rhetorical promise that these rights are supreme. The rights are asserted, but then they are hedged in by numerous exceptions. Some of these exceptions are necessary for the maintenance of good order and to balance the rights of the individual against the wider society. If, however, you expect a constitution to be a strong endorsement of the basic, core rights that individuals possess in your society -- the social contract between the person and the State – then the Jamaican Constitution does not play a particularly strong role.

(2) Human rights safeguards in the Constitution are undermined by savings clauses.

In a fundamental sense, the savings clauses in the Constitution serve to whittle away several human rights safeguards that the Constitution itself appears to grant. With respect to the rights in Chapter III, the most directly relevant savings clause is found in Section 26(8) of the Constitution. Section 26(8) reads as follows:

“Nothing contained in any law immediately before (the date of independence) shall be held to be inconsistent with any of the provisions of this Chapter; and nothing done under the authority of any such law shall be held to be done in contravention of any of these provisions.”

In summary form, this clause ensures that no law which was valid before the date of independence from Britain can be struck down as unconstitutional, or contrary to basic human rights law in Jamaica: pre-independence rules are sacrosanct, pre-independence human rights norms are preserved. This type of savings clause was probably adopted in the Jamaican Constitution (and in a number of other Caribbean Constitutions) as an administrative convenience to avoid uncertainty as to basic rights and freedoms with the coming of independence; and it may well have been assumed by the British authorities that that no pre-independence law was incompatible with basic human rights norms in any event. Given, however, that human rights standards can and do evolve with the passage of time, and that perceptions of human rights sometimes change to suit new social and philosophical approaches, it is undesirable to freeze human rights law in Jamaica in the terms of Section 26(8).

As presently structured, therefore, the savings clause provisions incorporate a deeply conservative approach to human rights law in Jamaica. If the British authorities or the Jamaican legislature restricted a certain human right before independence, then that restriction is still valid in 2008. The conservatism inherent in this approach may be readily demonstrated with reference to the question of flogging and whipping. The United Nations Convention on Torture, Cruel and Inhuman Treatment prohibits these forms of punishment. And yet, in a region that should reject flogging and whipping as part of the unwanted legacy of slavery, flogging and whipping may still be constitutional because they have been “saved”, either by Section 26(8) or by another savings provision pertaining to forms of punishment set out in Section 17(2) which states in essence that punishment that was not regarded as inhuman or degrading before independence retains this status in the post-independence period.

For example, in R v. Errol Pryce, a case from 1994, the Jamaican Court of Appeal upheld a sentence of whipping. Carey P (Ag.), writing for the court noted, among other things, that because the Crime (Prevention of) Act sanctioning whipping was in force before independence, it was preserved by Section 26(8). To be sure, in a more recent case, R v. Noel Samuda (1996), the Court of Appeal refused to uphold a sentence of whipping primarily on the basis that the statutory provisions in the instant case (the Crime (Emergency Provisions) Act of 1943), and subsequent provisions passed by reference thereto) were not actually in effect in Jamaica at the time the sentence was imposed. Significantly, though, in R v. Noel Samuda, a majority of the judges, Bingham J.A. and Harrison J.A. expressed views suggesting that the savings clauses in Sections 17(2) and 26(8) could be used to uphold flogging and whipping if these sentences validly existed before independence. In other words, the savings clause approach may still work to preserve flogging and whipping as long as it can be shown that these forms of punishment are sanctioned by existing legislation that predates independence.

This situation has prompted unequivocal criticism from the United Nations Human Rights Committee, as for instance, in the case of Errol Pryce:

“The Committee notes that the author was sentenced to 6 strokes of the tamarind switch and recalls its jurisprudence, that, irrespective of the nature of the crime that is to be punished, however brutal it may be, corporal punishment constitutes cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment contrary to Article 7 of the Covenant.” (paragraph 6.2).

The savings clause approach law has also played a role in ganja debate in this country. In August 2001, the Chevannes Commission on Marijuana recommended that ganja should be decriminalized when used in premises not accessible to the public. The Commission built its argument partly on the premise that marijuana use is such an integral part of Jamaica culture that there was little point in trying to maintain criminal sanctions against persons possessing small quantities of the drug. Some of you may know that I have resisted the main recommendations of the Chevannes Commission for a variety of reasons, and I continue to do so. The point for consideration here, however, concerns the fact that the Jamaican courts are, in effect, discouraged from reaching a decision on whether marijuana use amounts in some circumstances to the exercise of freedom of conscience or religion, and therefore supported by the Constitution. Various points may be made in this debate, including points about the weight to be given to freedom of religion versus other social values and concerns that ganja use may have serious negative effects on the wider community. But, this debate is not likely to receive full consideration in the courts because of the savings clause. Specifically, because the Dangerous Drugs Act precedes independence, the Jamaican Constitutional Court held in DPP v. Forsythe that the savings clause works to preserve the legislation from constitutional challenge on human rights grounds. The court relied on other grounds for upholding the Dangerous Drugs Act, including the notion that the Act is “reasonably required” to protect public health; it is fair to suggest, however, that but for the savings clause, there would have been a more extensive judicial consideration of the role of human rights principles in the marijuana debate.

Two further aspects of the savings clause approach may be highlighted here. Particularly in the early years after independence, judges in Jamaica were rarely called upon to assess the constitutionality of Acts of Parliament on human rights grounds; for, at that time, most laws were by definition pre-independence rules. Thus, it is arguable that there did not develop, with any great force, a jurisprudential tradition in laws are questioned in light of human rights norms. This is in contrast with, for example, the situation which was addressed by the South African Supreme Court in the first year following black liberation: in that case, S v Makwanyane, the South African Supreme Court was called upon to consider the constitutionality of the death penalty from first principles.

The very nature of the case, and the fact that there was no short-cut, conservative solution via a savings clause, has helped to affirm the importance of human rights analysis in South African jurisprudence from the outset. In the case of Jamaica, the situation is changing, and one notes in passing that, recently, in the case concerning the Portmore Toll Road and in the Trevor Forbes Case, concerning extradition, novel but ultimately unsuccessful arguments based on the human rights listed in Chapter III of the Constitution, were presented to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

Secondly, it is to be remembered that the savings clause does not work to save laws that have been passed since independence. In the case of Lambert Watson v. The Attorney General of Jamaica, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council held that the mandatory death penalty, as contemplated by Jamaica, was not preserved by the country’s savings clause because the law setting out the mandatory death penalty – the Offences Against the Person Act – had been amended following independence. For their Lordships, the savings clause is to be read restrictively, and amendments to pre-independence laws bring the entire pre-independence law within the purview of the courts. From a human rights standpoint this approach has value, for it limits the cases in which the savings clause will be applicable to laws that have remained untouched since 1962, a category which will diminish in size with the passage of time.

But, the Lambert Watson decision also highlights the paradox of pre-independence savings clauses. In this case, the relevant provisions of the law were amenable to constitutional review by the Privy Council only because the law had been amended in 1992. A law passed by the Colonial Power or by the Jamaican legislature before independence would, in effect, have greater binding force than one passed by the legislature of independent Jamaica. Nor is this a theoretical proposition. On the same day that the Privy Council delivered its judgment striking down Jamaica’s death penalty law, a law which had been intended to restrict the instances in which the death penalty was applicable, the same court upheld mandatory death penalty laws for Trinidad and Tobago and Barbados. The laws in the latter two countries applied the death penalty to a larger category of murders than the Jamaican law; those laws were held to be valid by a majority of the Privy Council essentially on the basis of the savings clause.

Overall, therefore, the promise of the Constitution, already limited by several restrictions in respect of particular rights, is further restricted by the existence of savings clauses. As a given society evolves, judges may well wish to consider whether human rights standards also change. Indeed, we are familiar with vibrant debates concerning the United States Supreme Court about whether judges, in interpreting a constitution, should apply the text and originalist conceptions of that text or whether they should assuming that the Constitution is a living document and thus eschew the so-called strict constructionism.

In the case of Jamaica, however, we are required to assume that pre-independence laws are always virtuous until the legislature indicates otherwise in new legislation. This undermines judicial creativity and places a premium on the past. It also helps to explain why for some areas of the law the basic human rights set out in Chapter III of the Constitution remain largely irrelevant.

(3) Some human rights rules in the Constitution need to be amended.

The question of constitutional reform has, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, been on the public agenda in Jamaica for at least thirty years. With respect to human rights issues, the draft Charter of Rights, which seeks to amend Chapter III of the Constitution in various ways, has come close to the port, but it is yet to arrive home. The draft Charter of Rights contemplates a number of important changes, and in some respects, demonstrates certain weaknesses in current human rights rules.

This is true, for example, in matters concerning discrimination on the basis of sex. Specifically, Section 24 of the Jamaican Constitution indicates that no law shall make any provision which is discriminatory; and discrimination is defined as placing persons at a disadvantage for reasons attributable wholly or mainly to their race, place of origin, political opinions, colour or creed.

It seems, therefore, that in some contexts it may still be possible to discriminate against women (or as is less likely, against men) simply on the basis of gender. Admittedly, this possibility is reduced by certain considerations. For one thing, there is actually some ambivalence in the terms of the Constitution. Although Section 24 rather pointedly fails to prohibit gender discrimination, another provision, Section 13 indicates that every person in Jamaica is entitled to fundamental rights and freedoms, regardless of race, place of origin, political opinions, colour, creed or sex.

The provision in Section 13 could ensure that as regards fundamental rights there can be no gender discrimination; but, Section 13 is preambular in its formulation, and there is a view to the effect that it does not actually create any rights and duties. Another factor that may reduce the possibility of State-supported gender discrimination arises from legislation. In the field of employment, Section 3(1) of the Employment (Equal Pay for Men and Women) Act indicates that no employer shall discriminate between male and female employees by failing to pay equal pay for equal work. There has been, of course, considerable debate on whether the requirement of equal pay for equal work actually ensures gender equality in matters of pay, and it may well be that a more appropriate standard would be equal pay for work of equal value, but it is fair to suggest that the Jamaican legislation acknowledges the principle of gender equality in this area.

Clearly, though, the Constitution needs to be amended to incorporate an unequivocal provision on gender equality. On this issue, Jamaican perspectives have certainly evolved since the time of the founding fathers, and if Jamaican society is to make progress and regard itself as fair and just, we cannot retain the implication of inequality in the legal document that reflects our highest aspirations and core values. This is one of the issues on which various sectors of Jamaican society appear to be in agreement.

In 1993, the Jamaican Constitutional Commission “unanimously and unhesitatingly” recommended that the word “sex” should be expressly included in the non-discrimination provision in Section 24 of the Constitution. There should be some degree of embarrassment in the fact that this is still to be done 15 years later. It hardly needs emphasis that if one half of the population is not firmly acknowledged as equal in the Constitution, some people will not take the Constitution seriously.

(4) The level of police killings suggests that, in some matters, agents of the State are prepared to disregard basic human rights.

The most basic human right is the right to life. The State has a duty not only to promote the security and safety of its citizenry, it must also ensure that its agents attach the highest significance to the right to life.

From a constitutional and legislative standpoint, the right to life may appear to be somewhat adequately safeguarded in Jamaica. This conclusion, however, would obviously be a deeply misleading representation of the overall picture concerning the right to life in the country; for, in practice, in Jamaica, the right to life is scarcely respected. Nor is this a recent phenomenon. Official statistics indicate that for the decade 1991 to 2000, 7,965 people were murdered in Jamaica, so that for each year about 796 people were killed on average. For the same period, agents of the State in the form of the police killed 1,389 persons (an average of about 139 persons per year), while 89 police were killed by civilians (an average of almost 9 per year). I have referred to the figures for an entire decade to demonstrate the pattern of murder, and to reconfirm, if reconfirmation is needed, that the question of murder constitutes a long-term, structural problem for Jamaican society.

Jamaica society is sharply divided on the question of police killings. On one side, many will argue that police killings amount to fundamental breaches of the right to life, with such killings being perpetrated as part of deliberate schemes for the destruction of persons perceived by State agents as criminal elements. In support of this viewpoint, the strikingly high level of police killings, the disproportion between police killings and the number of police killed by civilians and the fact that the level of police killings has been at a high level for over three decades, all suggest that the present situation is not accidental. So, for example, from September 1986, Americas Watch argued that both statistical patterns and individual cases suggest that the Jamaican police “seek out” crime suspects and “summarily execute them.” It is also suggested that some members of the security forces are prepared to take advantage of the high crime rate to kill civilians in the pursuit of political and terrorist agendas, private motives or to satisfy sadistic tendencies and other psychological problems.

In January 2008, Former Prime Minister Edward Seaga, referring to a raid by the security forces in which five people were killed, put the matter in these terms:

“In the absence of acceptable answers to the public (on specific questions posed), the conclusion could be drawn that there exists in the Jamaica Constabulary Force killer police who are irretrievably steeped in the deadly practice of state terrorism.”

On this side of the argument, local human rights groups have become increasingly vocal, and in some instances, have sponsored petitions to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights against the Jamaican State.

On the other side, State authorities in Jamaica have never acknowledged the existence of a policy of deliberate police killings, and have often argued in support of the rule of law. On occasion, some State officials have made statements that could be interpreted as supporting police murder, but some of these statements may also be read as affirmations of the right of self-defence for the police. Even so, however, the level of killings is high, and there is the perception among many that, given the level of criminality in the society, it is entirely understandable that the police should fight back. The wider societal view may well be that callous murderers should not be allowed to act with impunity, and that, in the present legal environment in which the death penalty has not recently been enforced, police killings are necessary to ensure justice with respect to known murderers.

Professor Don Robotham appears to accept it as given that the wider society is in favour of police killings that are not in self-defence; in the Gleaner of January 20, 2008, he wrote:

“Jamaican society cannot be asking security officers to take life with a wink and a nod, and then when they do exactly what we are demanding, throw our hands up in horror and turn around and berate them.”

Robotham also suggests that the security forces “must be heartily tired of the unbearable hypocrisy” of Jamaican society in respect of police killings, and argues that we need to put in place a “rights-governed framework” in which a special segment of the Jamaican judiciary will sit in judgment on security force operations such as that which took place in Tivoli Gardens in January 2008. As part of this scheme, Robotham would also change the rules of engagement so that security agents of the State could use force other than in circumstances of self-defence:

“The challenge is how to specify the situations in which lethal state violence is permissible, and to elaborate and operationalise an effective legal framework to regulate such situations. Let me be crystal clear here: I am referring to the right of the security forces to use lethal force in situations which do not meet the current legal standards of self-defence.”

In this debate, which concerns how security forces should operate in a high crime environment, the better view is that that State should be committed to respect for the right to life. Notwithstanding Robotham’s argument, the security forces should remember that they ought not to take life save in circumstances of self-defence. Whenever the police or soldiers take life for reasons other than self-defence, this not only violates the human rights of the victim, it also reinforces the notion that State agents are prepared to disregard human rights concepts, very often with impunity.

(5) There are other instances in which the State has not fulfilled its human rights obligations.

The issue concerning police killings provides the most visible reminder that in some instances the State has not fulfilled its basic human rights obligations to the people of Jamaica. But there are other examples of this problem. One of these concerns the treatment of persons who are incarcerated within the Jamaican prison system.

In the post-independence period, the Jamaican State has not accorded high priority to the construction and maintenance of prisons, other correctional facilities and detention centres. And, as a result, in many instances conditions at such facilities fall considerably short of elementary conditions for humanity: overcrowding at some facilities is both extreme in magnitude and enduring in character, some buildings are dilapidated, sewerage systems are often inadequate, and generally conditions are simply deplorable.

In these circumstances, it is difficult to argue that Section 17 of the Jamaican Constitution – which prohibits inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment -- is being respected. Of course there is the view that we need not be unduly worried about prison conditions, for, if prisons are too commodious, this may actually promote criminal activity. In reality, Jamaica is nowhere near this particular tipping point: in several prisons, we fall well short of the minimum standards in both law and morality. Against this background, the charge that the State is insensitive to some human rights standards is easily made.

(6) Questions concerning the death penalty have cast a long shadow over the human rights environment in Jamaica.

Of all the human rights questions facing Jamaica, the death penalty raises the most difficult and controversial issues in practice. The response of the international community to Jamaica, and more generally the Commonwealth Caribbean, on this issue has placed us in an invidious position. At times, the death penalty question dominates news about human rights developments in Jamaica, and the impression is engendered that some Jamaican authorities arbitrarily wish to carry out death sentences, influenced by fright, fear and social prejudice. This caricature does not do justice to the complex issues that have attended the death penalty debate both here and elsewhere in the Caribbean.

Both local and international opponents of the death penalty sometimes argue that the retention of the death penalty in Jamaica is inconsistent with International Law. Various European Governments take this position, as do non-governmental organizations such as Amnesty International and the much-respected Independent Jamaica Council for Human Rights. To support their position, these entities note various developments including the fact that the United Nations Human Rights Committee in its First General Comment on Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights maintained that some aspects of Article 6 “strongly suggest that abolition is desirable.”

By the same token, critics of the Jamaican position on the death penalty point out that the former United Nations Commission on Human Rights had repeatedly passed resolutions calling on States to abolish the death sentence, and emphasize that an increasing number of countries has, in fact, prohibited the sentence in practice. The decision not to incorporate the death penalty among the possible sentences available to the International Criminal Court and other international criminal tribunals has also been mentioned as evidence as to the appropriate way to handle this issue in human rights law.

Jamaica has therefore increasingly been called upon to defend its position in favour of the death penalty. In October 2007, the Government of Jamaica set out some of its arguments in a vote at the United Nations on the subject. For Jamaica, the death penalty is not prohibited in International Law. The governing rule of International Law is set out in Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This provision indicates that everyone has the right to life, and no one may arbitrarily be deprived of this right: given that the death penalty is judicially sanctioned in each case, it cannot reasonably be described as arbitrary. Other provisions of Article 6 have also been raised by Jamaica. So, for instance, Jamaica maintains that Article 6(2) clearly contemplates the possibility of the death penalty in some cases; it reads:

“In countries which have not abolished the death penalty, sentence of death may be imposed only for the most serious crimes in accordance with the law in force at the time of the commission of the crime and not contrary to the present Covenant and to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. This penalty can only be carried out pursuant to a final judgment rendered by a competent court.”

Likewise, Jamaica has argued that where Article 6(5) prohibits the imposition of the death penalty on persons below 18 years of age or on pregnant women, this is taken as convincing evidence that Article 6 does not bar the death penalty for persons falling outside the protected categories. Again, the assertion in Article 6(6) that nothing in Article 6 shall be invoked to delay or prevent abolition of the death penalty is itself presented as confirmation that Article 6 does not itself prohibit the death penalty.

Jamaica has also responded to the specific claims made by European countries outside the context of Article 6. For Jamaica, all the legal arguments raised by death penalty critics actually presuppose the lawfulness of the death penalty. So, for instance, where the United Nations Human Rights Committee indicates that abolition is desirable, this is taken as an acknowledgement that International Law will need to be changed if abolition is to become a requirement of the law. Jamaica has also argued that those treaties that expressly prohibit the death penalty, including the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights to Abolish the Death Penalty have not been widely accepted, and more importantly, have not been accepted as law by Jamaica.

From a positivist standpoint, Jamaica is correct. There is no binding rule of International Law that requires the abolition of the death penalty in all circumstances. At the same time, however, it may be that Jamaica has been heavily legalistic about an issue that has several moral and political undertones. Because of these undertones, there has been a steady flow of criticism of the general human rights record in Jamaica, when in fact the central point of tension has actually been the death penalty. In other words, because Jamaica has remained at least nominally in the retentionist camp on death penalty questions, the country may be the subject of more severe criticism about its human rights record than is warranted by the situation in the country. That is part the long shadow of the death penalty in Jamaica.

Another part of the shadow concerns the well-known line of Privy Council cases that includes Pratt and Morgan v. The Attorney General of Jamaica and Neville Lewis v. The Attorney General of Jamaica. In the former case, the Privy Council held that where, in capital cases, the time between the sentence of death and execution exceeds five years, “there will be strong grounds for believing that the delay was such as to constitute inhumane or degrading punishment or other treatment.” The Privy Council also found that where there was inhumane or degrading punishment or other treatment, contrary to Section 17 of the Constitution, the sentence of death should be commuted to life imprisonment.

One result of this decision was that it placed pressure on the State to ensure that all appellate procedures before the courts are completed in five years. In 1997, the Jamaican Government, when faced with the five-year time period, withdrew the country from the First Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as a means of expediting death penalty cases. This act prompted considerable criticism from lawyers and human rights activists. Jamaica had withdrawn from a multilateral human rights treaty, and in so doing, had placed itself in a small category of countries to have taken this step; the country had also removed itself from having the benefit of advice from the United Nations Human Rights Committee on a range of human rights questions, including, but not limited to, the death penalty. Again, arising from the death penalty question, Jamaica was represented being significantly against human rights.

The Neville Lewis Case has also had an important bearing on death penalty adjudication in Jamaica. To begin with, in this case the Privy Council appears to have converted the five-year presumption in Pratt and Morgan into an enforceable rule to the effect that once five years have elapsed between sentencing and execution, the death penalty is automatically to be commuted to life imprisonment. Also, in Neville Lewis their Lordships indicated that the State could not effectively place an upper limit on the time within which international human rights bodies could hear petitions in death penalty cases. Thus, if the Inter-American Commission were to take two years to respond to an individual petition, according to the Neville Lewis decision this would simply mean that the convicted person would stand a greater chance of having his sentence commuted than if the Commission were to take nine months to respond.

The upshot is that the Privy Council has created the opportunity for the Inter-American Commission to decide, in effect, who lives and who dies in Jamaican death penalty cases. In this regard, it should be recalled that in the Pratt and Morgan Case the Privy Council had estimated that it would take approximately nine months for petitions to be heard by each international human rights body.

A presentation by the previous Attorney General of Jamaica, A.J. Nicholson Q.C., indicated that of 18 cases involving the full procedure before the Inter-American Commission between 1994 and 2004, none took nine months or less, the shortest period was one year, and the longest was 3 years 5 ½ months. Seven cases took more than 2 years. This suggests that it may be somewhat difficult for Jamaica to carry out the death penalty unless ways are found to expedite the procedures of the Inter-American Commission. It has also been argued that some of the delay in death penalty petitions before the Commission has been prompted by tardiness on the part of the Jamaican Government; if this is the case, then the Government too will need to expedite its procedures in order to meet the five-year time limit. Notice, though, the wider point: in trying to accelerate the pace of the Commission’s work, and in trying to place time limits on the Commission, Jamaica was vulnerable to the charge that it wished to influence the decision-making procedures of an independent human rights body, not the kind of accusation that Jamaica could have welcomed.

(7) Advocates often invoke International Law as decisive in their human rights debates.

As is evident from aspects of the foregoing discussion, human rights rules normally apply at both domestic and international levels. In the case of Jamaica, most assessments of the human rights situation are undertaken with reference to domestic law, not least because individuals exercise their rights and undertake duties primarily with reference to Jamaican law.

Significantly, however, several Jamaican law rules overlap with human rights rules set out in treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the American Convention on Human Rights. This overlap should come as no surprise: as a matter of history, post-World War II human rights rules owe their origin mainly to the Universal Declaration on Human Rights of 1948.

This declaration, a resolution of the General Assembly of the United Nations, set the stage for the formulation of binding treaties such as the European Convention on Human Rights, and the ICCPR and the ICESCR, which were both open for ratification in 1966. Jamaica became independent in the period following the Universal Declaration and the European Convention on Human Rights, and it is clear that in preparing the Jamaican Constitution, the founding fathers relied heavily on the European Convention in identifying the human rights to be treated as fundamental. They incorporated, in particular, the civil and political rights in the European Convention as part of Jamaica’s domestic law.

In a sense, this significant overlap between Jamaican human rights rules and the International Law rules, as set out, for instance, in the European Convention and the ICCPR, has helped the Jamaica State to argue that the country is in the mainstream of international human rights law. But this overlap also carries other implications. One is that advocates in human rights cases are often inclined to cite international human rights developments to support their contentions on various points. This approach has its virtues; among other things, it should prompt us all to remain abreast of changes in International Law, and helps to reinforce the notion that at least some human rights norms are universally applicable. But, the tendency to rely on international human rights law may also carry certain pitfalls, and so, it may be appropriate to sound a warning that international human rights rules need to be applied with circumspection in the Jamaican context.

For a start, it is important to remember that the several economic and social rights set out in the ICESCR do not have the same binding character as civil and political rights. This is so because the ICESCR itself does not contemplate that that all its rules will have binding effect. This treaty lists rights such as the right to education, the right to physical and mental health, the right to work, leisure and the right to an adequate standard of living. Of course, these are important social objectives, and each State should be encouraged to ensure that they are satisfied.

It is difficult to argue, however, that these are objectives are always regarded in all societies as rights that are enforceable in court. The cost of securing these objectives may well be beyond the means of the typical developing country, and conceptually some people argue that human rights properly understood should be limited to acts of restraint by the State, that is, to civil and political rights. In any event, the ICESCR recognizes that some of the rights set out therein may not be immediately enforceable; thus Article 2(1) provides as follows:

“Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to take steps, individually and through international assistances and co-operation, especially economic and technical, to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the present Covenant by all appropriate means, including particularly the adoption of legislative measures.”

In short, the ICESCR leaves it to each country to determine the extent to which it will satisfy the objectives in that treaty: the fulfillment of these objectives is subject to the country’s available resources. This is not to suggest, for instances, that the right to education is unimportant; it is only to indicate that the extent to which a country fulfills this right is largely to be determined by that country. This point is sometimes not fully appreciated by those who argue that International Law ensures a right to tertiary education in all countries.

In some instances, persons invoke International Law as decisive in human rights matters when, in fact, International Law speaks with ambivalence. Consider the difficult moral, legal and philosophical question of abortion. The Abortion Policy Review Advisory Group in Jamaica has formulated certain recommendations that, no doubt, will be the subject of considerable debate in society. To what extent does international human rights law govern the question of abortion? To date, both advocates and opponents of abortion rights have invoked international treaties to support their divergent perspectives. In some respects both sides are correct, which is another way of saying that international law does not speak decisively on the subject.

More specifically, the ICCPR enshrines the right to life, but it does not indicate the point at which life begins. At one point in the negotiations on the ICCPR, in 1957, five countries (Belgium, Brazil, El Salvador, Mexico and Morocco) proposed language to the effect that “from the moment of conception” the right to life “shall be protected by law”. This proposal was expressly opposed by some States and when the matter was put to a vote, the proposal was rejected by 31 to 20, with 17 abstentions. Thus, the ICCPR does not expressly incorporate what some may characterize as a “pro-life” perspective; and given that the pro-life approach was considered and rejected, one could conclude that the ICCPR does not support that approach. On the other hand, as Shirley Richards of the Lawyers Christian Fellowhip reminded us recently, the American Convention on Human Rights, to which Jamaica is a party, takes a different approach. Article 4(1) of the latter convention states that:

“Every person has the right to have his life respected. This right shall be protected by law and, in general, from the moment of conception. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life.”

This provision embraces the view that life begins at conception, and therefore serves, at least as a starting-point for the pro-life perspective in abortion matters. If, therefore, Jamaica were to contemplate a permissive regime for abortion, it would be necessary to reconcile that approach with the country’s treaty obligations under the American Convention. But, the matter does not necessarily end there; for Jamaica would also need to take into account the approach taken by the Inter-American Commission in the Baby Boy case. In this case, a majority of the Inter-American Commission rejected the idea that Article 4(1) prohibited abortion in all circumstances. The majority noted that Article 4(1) represented a compromise between States which waned the right to life protected from conception and those which had laws permitting abortion for a number of reasons, and emphasized that the use of the phrase “in general” in Article 4(1) could possibly allow abortion in cases of rape or to save the mother’s life, among other possibilities.

Hence, Article 4(1) of the American Convention holds that conception begins at birth, but the precise implications of this provision are not altogether clear because of the “in general” formulation. At a time when there are suggestions that Jamaican law already allows abortion in some circumstances, and countervailing positions on this point, we would probably have been happy to have clear guidance from international law. But like national law, international law reflects the uncertainties in this area, and so, assertions about what international law says about abortion need to be considered with care.

Two further warnings need to be mentioned about the relationship between international law and Jamaican law need to be mentioned briefly. In the first place, where Jamaica is a party to a treaty, the provisions of that treaty are binding on the country at the international level. So, for instance, Jamaica has accepted that human trafficking is contrary to international law, and has undertaken at the international level to take certain measures to discourage such trafficking. If Jamaica does not introduce those measures, then the country will be in breach of its obligations to other parties to that treaty, at the international level. It is important to note, however, that when Jamaica becomes a party to a treaty, this fact does not in itself give rise to rights and duties within Jamaican law. In the normal case, Jamaicans will not enjoy the rights set out in a treaty unless and until those rights are incorporated into domestic law, usually by an Act of Parliament. This principle is well-established in the law; in Chung Chi Cheung v. R , Lord Atkin explained it as follows:

“It must always be remembered that, so far, at any rate, as the Courts of this country are concerned, international law has no validity save in so far as its principles are accepted and adopted by our own domestic law. There is no external power that imposes its rule upon our own code of substantive law or procedure.”

This rule has had various implications in Jamaican law, and with respect to both the Privy Council and the Caribbean Court of Justice, some judges appear inclined to find exceptions when death penalty questions are involved. The point here, however, is that the rule exists, and it is not open to the Jamaican Government to disregard it. As a result, human rights advocates should seek to ensure that the State follows through on its obligations by bringing into domestic law the treaty rules that they accept at the international level.

Secondly, it is important to note that although treaty rules are binding on States Parties, the interpretations given to those rules by human rights bodies such as the United Nations Human Rights Committee and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights are recommendations, and as such, are not binding rules of law. Naturally, these recommendations are to be accorded considerable respect as they reflect third-party assessment of the human rights situation in various countries, and as the various bodies have developed significant expertise and authority in interpreting particular provisions of human rights law. But it may also be that in some situations a country may decide not to accept the recommendations of the human rights body for a variety of good reasons.

Generally, the point may be illustrated by two examples. The first concerns the case of Frank Robinson v. R. In this case, the appellant was convicted of murder and sentenced to death, when, faced with the prospect that the main prosecution witness would disappear, the trial judge had insisted upon proceeding with the case, even though the appellant was unrepresented. Prior to the commencement of the trial, the case had been adjourned on 19 previous occasions, owing to the absence of the main prosecution witness. On the 20th occasion, with the witness present, the trial judge started the case even though counsel for the appellant were absent. On the following morning, counsel for the appellant both withdrew from the case apparently because they had not been fully paid. The case proceeded and the appellant was convicted. On the question of whether the appellant had been accorded a fair trial, the Privy Council considered Section 20(6) of the Jamaican Constitution, which provides:

“Every person who is charged with a criminal offence –

(c) shall be permitted to defend himself in person or by a legal representative of his own choice.”

The Privy Council concluded that that word “permitted” in Section 20(6)(c) indicated that the State could not prevent the appellant from having counsel of his own choice, but the provision did not “give rise to an absolute right to legal representation which if exercised to the full, could all too easily lead to manipulation and abuse.” Thus, Mr. Robinson could be executed, even though he was unrepresented in the murder trial.

The United Nations Human Rights Committee disagreed with the Privy Council’s approach. The Committee noted that “it is axiomatic that legal assistance be available in capital cases”, and held that this should be so even where the unavailability of private counsel “is to some degree attributable to the author himself” and even if an adjournment of the proceedings is necessary to secure legal assistance to the accused.

In my opinion, the Human Rights Committee correctly placed greater emphasis on the trauma and unfairness inherent in requiring the accused to defend himself personally in a capital case, than upon whatever risk the State may face if an adjournment is offered in particular cases. The local Privy Council accepted the recommendation of the Human Rights Committee and Mr. Robinson’s sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. The case for accepting the recommendation of the Human Rights Committee in this case is easily made.

The case of Robinson, where a recommendation is readily acceptable, may be contrasted with the situation concerning corporal punishment for children. Most Jamaicans, and other Commonwealth Caribbean nationals, believe that corporal punishment for children should be permitted in some circumstances. In a recent study, Joan Durrant found that 96% of Caribbean nationals surveyed believe corporal punishment reflects parents’ “caring enough to take the time to train the children properly”, 71% generally approve of parental corporal punishment, and 69% believe that corporal punishment is a good and normal part of raising children.

On the other hand, various human right agencies within the United Nations, including the Human Rights Committee, the Committee on the Rights of the Child, the Committee against Torture, and the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights maintain that corporal punishment for children is contrary to the inherent dignity of the child, and to the terms of treaties such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the ICCPR. Thus, there is a significant gap between the Caribbean cultural perspective on corporal punishment and the recommendations of the United Nations.

In these circumstances, there is a strong case to be made that recommendations from the United Nations are only recommendations, and that it would be culturally inappropriate to apply them without qualification in Jamaica. Some human rights standards may well be universally applicable, but where a human rights body applies a broad interpretation to a treaty provision, and thus adds new meaning to the provision, that body should understand that not all countries will accept its interpretation.

Conclusion

This discussion has considered some of the factors that influence the human rights project in Jamaica. In recent years, notions of human rights have come to play an increasingly important role in our lives. This is as it should be, for we exist in a society governed by laws, and we proceed from the premise that the authority that the State holds over individuals is derived from those laws. The Constitution of Jamaica plays a prominent role in restricting State abuse, and must naturally be the starting-point for any assessment of human rights safeguards in the country. Chapter III of the Constitution, which sets out a list of our fundamental rights and duties largely reflects the consensus in Western societies the scope of basic human rights.

But the Constitution is vulnerable to criticism on various counts. To be sure, it is not deeply problematic in the way that some commentators suggest, but it should be reformed to ensure that its language more fully reflects the modern aims, aspirations and values of the Jamaican people. In its reformulation, we need to be careful to balance the rights of the individual versus the rights of the wider society, but the actual language and structure of the revised Constitution should show more clearly the significance that the State attaches to individual rights.

In this regard, the savings clause in the Constitution, which preserves pre-independence laws from challenges based on principle, has now outlived its usefulness and needs to be removed. And, at the same time, the language of the revised Constitution must make it abundantly clear that unfair discrimination on grounds of gender is contrary to basic principles of Jamaican society.

With respect to some issues, the Constitution may speak with clarity and yet some agents of the State disregard its terms. Some of these issues arise directly out of Jamaica’s high crime rate and the country’s penchant for deadly violence. There is widespread disrespect for the most basic right – the right to life – and this manifests itself not only in the monstrously high murder rate, but also in the disproportionate number of civilians killed by the police. A pastor has recently said “we too thief”, and to this I would humbly add “we too murderous”.

As the society continues its search for solutions to the problem of murder, we should be careful that we combat the tendency for agents of the State do not adopt the methods of those who would destroy the society. This is not a statement of hypocrisy; it is an acknowledgement that those who believe in law and order have principles; we are different from murderers, and we must not embrace their methods. We value the right to life, and so, we support police killings only in circumstances of self-defence.

In the assessment of human rights, there are various technical issues that do not normally come to the fore in general reviews of the situation in Jamaica. Among other things, we need to remain mindful of the possibility that the approach taken to the death penalty in Jamaica has cast a long shadow on the country’s human rights terrain. Although some countries argue to the contrary, Jamaica has maintained with some force that the death penalty is not in itself inconsistent with International Law. It is important to note, however, that because Jamaica retains the death penalty, the country has remained subject to greater scrutiny on human rights questions than others. The actions that Jamaica has had to take in its attempt to satisfy the terms of the Pratt and Morgan decision, in particular, have also prompted the view – not fully sustained -- that Jamaica is not fully committed to human rights principles.

Finally, various issues concerning the interplay between international law and national law arise in the assessment of Jamaica’s human rights situation. International law and domestic law constitute separate spheres of law, but they overlap in significant ways. In the area of human rights there is a tendency to argue that certain ideas prevalent at the international level are automatically part of local law. The matter is, however, more complex than that. It is also to be remembered that international human rights bodies make recommendations and do not present binding decisions. This is significant: recommendations allow the State some leeway in its consideration of whether to adopt an external approach that may, or may not, be consistent with domestic public policy.

Welcome to my blog

The rule of law in Jamaica is under serious threat, following the government's opposition to the appointment of Stephen Vasciannie as Solicitor General of Jamaica, and its subsequent dismissal of the Public Service Commission for alleged "misbehaviour".

Under Jamaica's constitution, the Public Service Commission has the exclusive authority to select persons for appointment to positions in Jamaica's civil service. The Solicitor General is one such position. The Solicitor General has overall administrative responsibility for the running of the Attorney General's Department. The Attorney General is appointed directly by the Prime Minister, and is therefore a political appointee.

In October 2007, Stephen Vasciannie was selected by the PSC for appointment as Jamaica's next Solicitor General. Contrary to Jamaica's constitution, Prime Minister Bruce Golding opposed the selection of Stephen Vasciannie as Jamaica's next Solicitor General. When the PSC refused to back down from its recommendation of Stephen Vasciannie, the PM dismissed the members in mid-December 2007. The Prime Minister claimed that he was dismissing the PSC members for "misbehaviour". Dismissal for "misbehaviour" is possible under Jamaica's constitution. However, the grounds of misbehaviour cited by the PM appear at best to be tenuous, and at worse, a cynical attempt to corrupt the autonomy of the PSC. The dismissal of the PSC has been challenged in the Jamaican courts by the Leader of the Opposition. I note with satisfaction that four of the five PSC members filed suit against the Prime Minister at the end of January 2008. Unfortunately, full trial is not scheduled until December 2008, primarily, if not solely, at the behest of the lawyers representing the AG and PM. In this respect, I do believe that the judiciary has dropped the ball in allowing the hearing to be deferred for so long.

[Editorial note-December 08, 2008- the litigation has now been settled]

I will post a number of news paper stories and articles that have been published on this issue, as well as other relevant information, such as the constitutional provisions that govern the PSC. I will also offer commentary from time to time on developments as they arise.

Most importantly, I do hope that interested Jamaicans and others will use this blog as a forum for the exchange of information and views. Needless to say, disagreement is more than welcome, but not disrespect.

Under Jamaica's constitution, the Public Service Commission has the exclusive authority to select persons for appointment to positions in Jamaica's civil service. The Solicitor General is one such position. The Solicitor General has overall administrative responsibility for the running of the Attorney General's Department. The Attorney General is appointed directly by the Prime Minister, and is therefore a political appointee.

In October 2007, Stephen Vasciannie was selected by the PSC for appointment as Jamaica's next Solicitor General. Contrary to Jamaica's constitution, Prime Minister Bruce Golding opposed the selection of Stephen Vasciannie as Jamaica's next Solicitor General. When the PSC refused to back down from its recommendation of Stephen Vasciannie, the PM dismissed the members in mid-December 2007. The Prime Minister claimed that he was dismissing the PSC members for "misbehaviour". Dismissal for "misbehaviour" is possible under Jamaica's constitution. However, the grounds of misbehaviour cited by the PM appear at best to be tenuous, and at worse, a cynical attempt to corrupt the autonomy of the PSC. The dismissal of the PSC has been challenged in the Jamaican courts by the Leader of the Opposition. I note with satisfaction that four of the five PSC members filed suit against the Prime Minister at the end of January 2008. Unfortunately, full trial is not scheduled until December 2008, primarily, if not solely, at the behest of the lawyers representing the AG and PM. In this respect, I do believe that the judiciary has dropped the ball in allowing the hearing to be deferred for so long.

[Editorial note-December 08, 2008- the litigation has now been settled]

I will post a number of news paper stories and articles that have been published on this issue, as well as other relevant information, such as the constitutional provisions that govern the PSC. I will also offer commentary from time to time on developments as they arise.

Most importantly, I do hope that interested Jamaicans and others will use this blog as a forum for the exchange of information and views. Needless to say, disagreement is more than welcome, but not disrespect.

Wednesday, January 30, 2008

The Cobb Family Lecture-The Human Rights Project in Jamaica- by Prof. Stephen Vasciannie

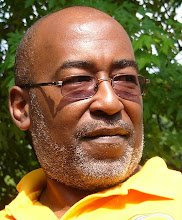

Posted by

Hilaire Sobers

at

7:52 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: human rights, Stephen Vasciannie

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment